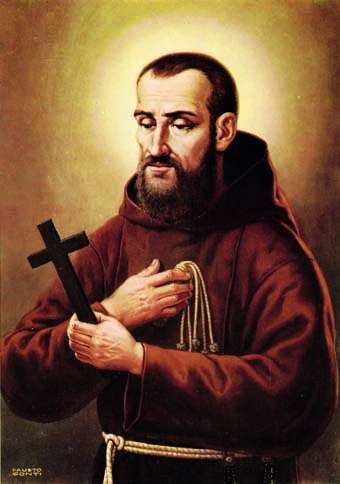

Saint Bernard of Corleone

Sword Fighter Joins the Capuchins

Still part of the popular imagination based on an old biography (Dionigi da Gangi OFM Cap., Dalla spada al cilizio: profilo del b. Bernardo da Corleone cappuccino, Tivoli, Mantero, 1934) is the distorted figure of Bernardo da Corleone as a troublemaker in the piazza, ever ready to come to blows with his unsheathed sword. Someone who lived in the Italian religious seventeenth century, wrongfully judged as formalistic, has even wanted to see in him the famous Father Cristoforo of the Manzoni novel, defender of the faith and of the oppressed. However Filippo Latino, as he was called before becoming a friar, was not Ludovico the swordsman of I Promessi Sposi.

One day in 1756, after disappointing results in his philosophy studies, the young José Francisco López-Caamaño y García Pérez entered the church of the Capuchin friary in Ubrique in Spain. The friars were chanting the Liturgy of the Hours. He got a start. As he later wrote in one of his letters, “My soul was filled with such a great joy and such an usual admiration that I nearly came out of myself.” He felt a great repugnance towards religious life, particularly Capuchin life, but in that moment he felt attracted and his enthusiasm was irrepressible. “I asked for a biography of any saint of the Order and they gave me one about our saints Fidelis and Giuseppe da Leonessa. Both were missionaries. Then they gave me a life of the venerable Br. José da Carabantes, the so-called apostle of Galicia. This made my heart burst into flames. Although I was only thirteen years old I longed for solitude, union with God, mortification, etc. Overcome by these desires, without consulting anyone, girded my waist and legs so tightly with rope that unable to breathe and walk I would have to take off one and loosen the other. I wore them for many days.” This youthful ardour led him to be clothed in the Capuchin habit in Sevilla on 12 November 1757. At fifteen years age he began the novitiate on 31 March 1758 with a new name, Diego José. “From that moment it was my ardent desire to be a Capuchin, a missionary and a saint. I even had the ambition to give my blood in martyrdom.”

Born in Corleone, “animosa civitas,” (A proud, courageous city) on 6 February 1605 impatient under Spanish domination, he had that from that fair and proud Sicilian city that generous and strong character, always ready to help and defend the poor. His home was, in the local parlance, a “home of saints.” His father Leonardo was good shoemaker and leatherworker. He was merciful with the needy, even to the point of bringing them home to wash, clothe and feed them with exquisite charity. His brothers and sisters were also known as persons of great virtue. Such fertile soil could not but bear positive fruit in the religious and moral formation of the young Filippo. Quite young he was very devout to the Crucified and the Virgin, and assiduous in prayer and the sacraments in the local churches. Above all his management of the shoemaker’s shop he treated the workers well and was never ashamed to seek alms “throughout the city during the winter for the poor prisoners.”

He had just one defect, according to two witnesses during the investigation. He easily became inflamed and quickly put his hand to the sword when provoked, especially in defence of his neighbour. His ‘hot’ temperament used to worry his parents, especially when he wounded the hand of a proud provocateur. However the public duel with the hired assassin Vito Canino in 1624 when Filippo was nineteen years old caused a furore. The assassin left us an arm and Filippo, considered the ‘best swordsman in Sicily’, was cut to the quick. He asked forgiveness of the injured man and the two would later become friends. His religious vocation matured into a salutary crisis that only resolved when, on 13 December 1631, he donned the Capuchin habit in the novitiate at Caltanissetta, choosing the friars closest to the ordinary classes. He was about twenty seven years old and wanted to be called Br. Bernardo.

His Capuchin life was a crescendo of virtue. He lived in various friaries in the Province – Bisacquino, Bivona, Castelvetrano, Burgio, Partinico Agrigento, Chiusa, Caltabellotta, Polizzi and probably also in Salemi and Monreale. However it is difficult to determine an exact chronological sequence. We do know that he spent the last fifteen years of his life at Palermo where he met sister death on 12 January 1667. It seems that shortly after his profession of vows we would have been in Castronovo and that he may have been in Corleono also a few years before his final assignment to the friary at Palermo. We never see him as porter or questor. His service was almost exclusively that of cook or cook’s assistant. To this he added care of the sick and other tasks in order to be useful to everyone – to friars overburdened with work, and washing the clothes of the priests. He became the launderer for nearly all his confreres. Such a disarming simplicity of life, in a humble and hidden corner in little Capuchin friaries did mean that his presence went unnoticed. The fragrance of his virtue soon went beyond the walls of the friary. Facts and deeds, often heroic, not to mention incredible penances and mortifications form an objective and considerable expression of his spiritual makeup.

The witnesses at his processes make abundant reference to the his tenor of life and are a splendid account of the particular characteristics of his personality: gentle and strong like his homeland: “He always exhorted us to love God and to do penance for our sins.” “He was always intent on prayer … When he entered the Church he feasted lavishly on prayer and divine union.” Then the time would go and often he remained behind in rapt ecstasy. After the recitation of matins at midnight, Br. Bernardo used to stay in the church because,” as he explained, “it was not good to leave the Blessed Sacrament on its own. He would keep it company until the arrival of other friars.” Even when he was cook or had other duties he found time to help the sacristan so as to stay as close as possible to the tabernacle. Contrary to the custom of the day he used to receive daily Communion. Finally, when he was exhausted by his continuous penances, the superiors entrusted to him the task of being solely at the service of the altar.

A genuine Capuchin, he was nostalgic for the past, fascinated and attracted by the experience “of the eremitical life”, almost plunging himself into the setting of the first Capuchins. He often used to be seen “to go into the forest in the direction of the Hermitage near the chapel of Our Lady where he went pray.” He expressed his love for Our Lady in a thousand ways. He built, in the kitchen, a little altar usually dedicated just to Our Lady (a widespread practice among the Capuchin cooks). During spare moments he had the joy of intimate prayer. He would then decorate this little altar “with flowers and fragrant herbs” – not only on Marian feast-days but also every Saturday. It was almost as if he had wanted to refresh the Blessed Mother with those perfumes.” An irrepressible joy accompanied his Marian devotion that was so full of warmth, creativity and celebration. And so it was on one occasion that when he was in his cell praying the Marian litanies, at the invocation of the ‘Holy Mary’ as one witness reported, “he made sounds like fireworks, as if it were a great solemnity.” Amused, the friars who heard him smiled and said, “Br. Bernardo is imitating the little children.”

Wherever he was – in the church, choir or refectory – as soon as he heard uttered or sung the words “Gloria Patri” he used to prostrate himself on the ground and kiss it with deep respect. In love with the Passion of Christ, his little crucifix painted simply on a wooden cross was very precious to him. It was the book he learned to read, putting an end to an attempt to study a primer – since he was illiterate – under the guidance of Br. Benedetto da Cammarata. For the Lord himself, appearing to Bernardo, said to him, “Bernardo, don’t look for what books contain because my wounds are enough for you. In them you will find that much more useful teaching than everything all the other books might communicate to you.”

He preferred the friaries that had a “good Crucifix.” The witnesses were unanimous here too. “He happily stayed in fraternities where the church had an image of the Crucified Christ.” He himself often said to the friars, “When you have a beautiful and devout Crucifix in the friary, there is nothing else you could desire.” He advised many friars to pray Saint Bonaventure’s Office of the Five Wounds of Christ. With his heart continuously focused on the mysteries of the Passion he experienced that “the Passion of the Lord” (in his own words) is a bottomless sea because it contains a great multitude of mysteries that incite the soul to the love of God.”

What impresses a modern reader is his extraordinary penance. It may be said that he transformed the entire year into a continuous Lent. He only ate blackened crusts and little morsels of hard, leftover bread dipped in water flavoured with bitter herbs. He always ate while kneeling on the floor behind the refectory door, using a chipped bowl with a rag for his napkin. He even did this when there were important guests. If a superior commanded him to take part in the common meal he would do so, but it was as if he had eaten poison because he would become ill and run a fever. But the Lord consoled him in this too. One day He appeared to him. Taking a little piece of that hard bread, he dipped it into the blood of His side and put it in Bernardo’s mouth, saying, “My son, persevere to the end in the life of abstinence.”

A fragrant blossom of this austerity was his chastity. He usually said, “Sorrows pass quickly but purity of heart and religious virtues are real lines upon the soul.”

It is not necessary to describe his other modes of ruthless penance. One thing is certain. With is ‘inhuman’ life, he had a delicacy and gentle attentiveness to others, a joy and fullness of life that was impressive. He was never seen “angry with anyone, or to complain, or murmur against his neighbour.” He never spoke ill of anyone. In fact he was never aware of the defects of others. He made a feast for visiting friars. He washed their feet and served them, while repeating like an antiphon, “For the love of God. For the love of God.” His great ability to console the troubled was well known. He was always available for the poor. However, if they became curious, even if they were people of standing, he could not be found anywhere. However he said to the brother porter, “When the poor come for me to see them, let me know straight away.” In Castronovo he used to go through the streets “with a large pot on his shoulders to give minestrone to the poor.”

He had a very maternal heart for the sick. His compassion was inexhaustible. His joy was to assist and serve them. When the entire fraternity in Bivona was struck by an epidemic he multiplied his charitable efforts both night and day. However, with all his strength exhausted, he had to succumb to illness, to the great desolation of the superior, deprived of his infirmarian. The doctor gave Bernardo less than a day to live. Br. Bernardo dragged himself in hiding to the church. He took from the tabernacle a decorative statuette of Saint Francis. He put it in his sleeve and challenged him. “Seraphic Father, I am letting you know that you will not leave my sleeve until you have healed me.” The following day he was perfectly well. When the doctor came to verify the death he was stunned and wanted to know about the miraculous medicine that had been used. Br. Bernardo took from his sleeve the statuette and with evident delight said, “Do you see? He healed me.!

Another time, in the friary in Castronovo, he knew that the Guardian was ill. As cook and infirmarian he thought to prepare for a more substantial meal. When he was out on the streets of the town he asked from a lady benefactor of the friary the charity of chicken for a more flavoursome soup. When he arrived in the kitchen the chicken had already been plucked and cleaned. As he was placing the chicken in the water over the fire, the guardian came in. Realising what had happened, he reprimanded Br. Bernardo and commanded him to give back the chicken immediately. In silence, Br. Bernardo wrapped it and hid it under his mantle and took it back to the benefactor with a brief and humble explanation. However, as he was giving her the chicken, it came back to life, and flew off crowing into the large room while. Finding the door of the chicken coup open, she joined the other hens and occupied the nest where she usually laid her eggs. Confused, Br. Bernardo sneaked off while the women present cried out aloud at the miracle. The din was so loud that many people came to see the resuscitated chicken, now named ‘Bernarda” by its owner.

His solidarity with his confreres embraced a social dimension. In the calamitous circumstances of earthquakes and hurricanes of Palermo, he became a mediator in front of the tabernacle, struggling with Lord like Moses: “Lord, ease up. Show us mercy! Lord, I want this grace, I want it.” The scourge stopped and the catastrophe abated.

His compassion towards every kind of suffering also included animals. When he came across an injured or sick animal, especially mules, horses, cows, donkeys – the guarantee of work for the poor at the time – he applied himself to heal them. Consequently on some days there were so many animals in the little piazza of the friary that it would look like a livestock market or a rather unusual first aid station. He would say an “Our Father” or lead the animal by the halter or by the horn three times around the big cross in front of the friary at Palermo while invoking the name of Jesus. Then each owner would take back his animal completely cured.

Once, however, the porter lost patience and protested with him. He told him that in the final analysis Bernardo’s task was not with beasts but with persons. Asking forgiveness, Br. Bernardo added, “My dear porter, these poor creatures of God have neither doctor nor medicine available to them. Since they cannot make their needs known, compassion is needed and we can put up with a little inconvenience to relieve their sufferings.”

Since he was a propagator of miracles the devil battled hard with him even since novitiate. However, with his humility, patience and wooden crucifix he always won. On his death bed he was impatient to get underway to his heavenly homeland. On receiving the final blessing he repeated joyfully, “Let’s go, let’s go” and breathed his last. It was 2 p.m., Wednesday 12 January 1667. A close confrere, Br. Antonio da Partanna, saw him in the spirit. Bernardo was shining and repeating, “Heaven! Heaven! Heaven! Blessed the disciplines! Blessed the vigils! Blessed the penance! Blessed the denials of my own will! Blessed the acts of obedience! Blessed the fasts! Blessed all the practices of religious perfection!” Saint Bernard Latini of Corleone was canonised by Saint John Paul II in 2001.

Translation based on Costanzo Cargnoni, Sulle orme dei santi, Rome, 2000, p.11-20.

PRAYER

God our Father, you have given us blessed Bernard as a wonderful example of penance and of Christian virtues. By the power of your Spirit make us firm in faith and effective in our work. We ask this through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.God our Father, you have given us blessed Bernard as a wonderful example of penance and of Christian virtues. By the power of your Spirit make us firm in faith and effective in our work. We ask this through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.