History of the Capuchin Philippine Province

For those who would like to know more about the Capuchin Province of Our Lady of Lourdes, the following texts provide a detailed history of the Capuchin Franciscans in the Philippines. This history was written by BFor those who would like to know more about the Capuchin Province of Our Lady of Lourdes, the following texts provide a detailed history of the Capuchin Franciscans in the Philippines. This history was written by Br. Joseph Nacua, O.F.M.Cap. D.D.

Back in the last quarter of the 1800s, there was only one Commissariate of the Capuchins in Spain owing to the suppression of monasteries and religious houses by governments influenced by the ideas that spawned the French Revolution. But the restoration of the Capuchin Order with the election of the Swiss General Minister, Fr. Bernard Christen of Andermatt, gave a new impetus to its expansion. Thus, it is within this larger historical framework that the Capuchins were finally reach the farthest outpost on the waning Spanish empire.

Owing to the peculiar Church-State relationship of the Spanish experience concretized in the Patronato Real de las Indias, it was by request of the Spanish royal government to send missionaries to its overseas possessions in order to preserve the Pacific islands from the German expansionistic ambitions. That the Capuchins sent the first expedition on board the vessel SS ‘Isla de Panay’ that set sail from the port of Barcelona on April 1886. They disembarked on Philippine soil in Manila, the gateway to the wider expanse of Asia and of the Pacific after a month on May 13, 1886.

As a footnote to this historic milestone, it may be remarked that the Capuchins were coming into the country just when other missionaries of various Congregations were leaving to return to their country of origin because of the gathering socio-political last quarter storm in the 19th century that culminated in the upheaval and turmoil of the Philippine revolution against the crown of 1898. It might also be noted that list of the first band of twelve Capuchin missionaries manifests a diversity of regional characteristics owing to geographical provenance. Very noteworthy also is the fact that there were six lay-brothers and six priests in the first group of missionaries.The list of names and their geographical pertinence may be appreciated in the following: Fr. Daniel de Arbecegui (Vizcaya) Fr. Agustin de Ariñez (Alava) Fr. Saturnino de Artajona (Navarra) Fr. Antonio de Valencia (Valencia) Fr. José de Valencia (Valencia) Fr. Fidel de Espinosa (Castilla) (died in transit) Br. Gabriel de Abertesga (Orense) Br. Eulogio de Quintanilla (Valencia) Br. Antolin de Orihuela (Valencia) Br. Miguel de Gorriti (Navarra) Br. Benito de Azpa (Huesca) Br. Crispin de Ruzafa ( )

A quote from the Chronicle of Fr Antonio de Valencia may provide for an imaginative reconstruction of the arrival of the first band of Capuchins:

“On May 13, 1886, at 6:30 in the morning, we arrived in Manila. The first convent we came upon was that of St. Dominic from where we then proceeded to the convent of St. Francis, accompanied by our Dominican and Franciscan brothers. A joyous ringing of bells of the church of the V.O.T. (Venerable Orden Tercera) of our seraphic Father announced to the people our arrival at the convent… we attracted much attention from the people of Manila because of our course and thick habits, sandals, our tonsure, and above all because of our long beards. Once the ceremonies of the official welcome were over, the eleven missionaries stayed at the convent of St. Francis, where we were treated with exquisite solicitude and fraternal charity by the Franciscan brothers.”

Plantingthe seeds.

After staying for some time with the Franciscans, six missionaries continued the journey to their destination: the Carolines and the Palaos islands. Thev other five remained with the Franciscans until they given charge of the spiritual needs of the people of Gagalangin and Tondo where they lived in a nipa-thatched hut. When Fr. Llevaneras, who later was raised to the Cardinalate, himself came the following year of 1887 for the canonical visit to Manila, the Carolines and Palaos, bhe was convinced of the necessity of establishing a permanent central office or a so-called “procura house” based in Manila in order to attend effectively to the needs of the missionaries scattered among these islands. A search for suitable place resulted a certain quality of “itinerancy” among the five who remained in Manila. From Tondo, they were able to rent a small house at San Marcelino street. Not long afterwards, they moved to Muralla Street in Intramuros, then to San Rafael Street, then to Solana Street, and then finally settled in Gen. Luna Street where they would definitively and canonically build the first Capuchin house and a church dedicated to Mary, the Mother of the Divine Shepherd. Six years had now passed when the church of the patroness of the Spanish Capuchin missions was dedicated on May 8, 1892.

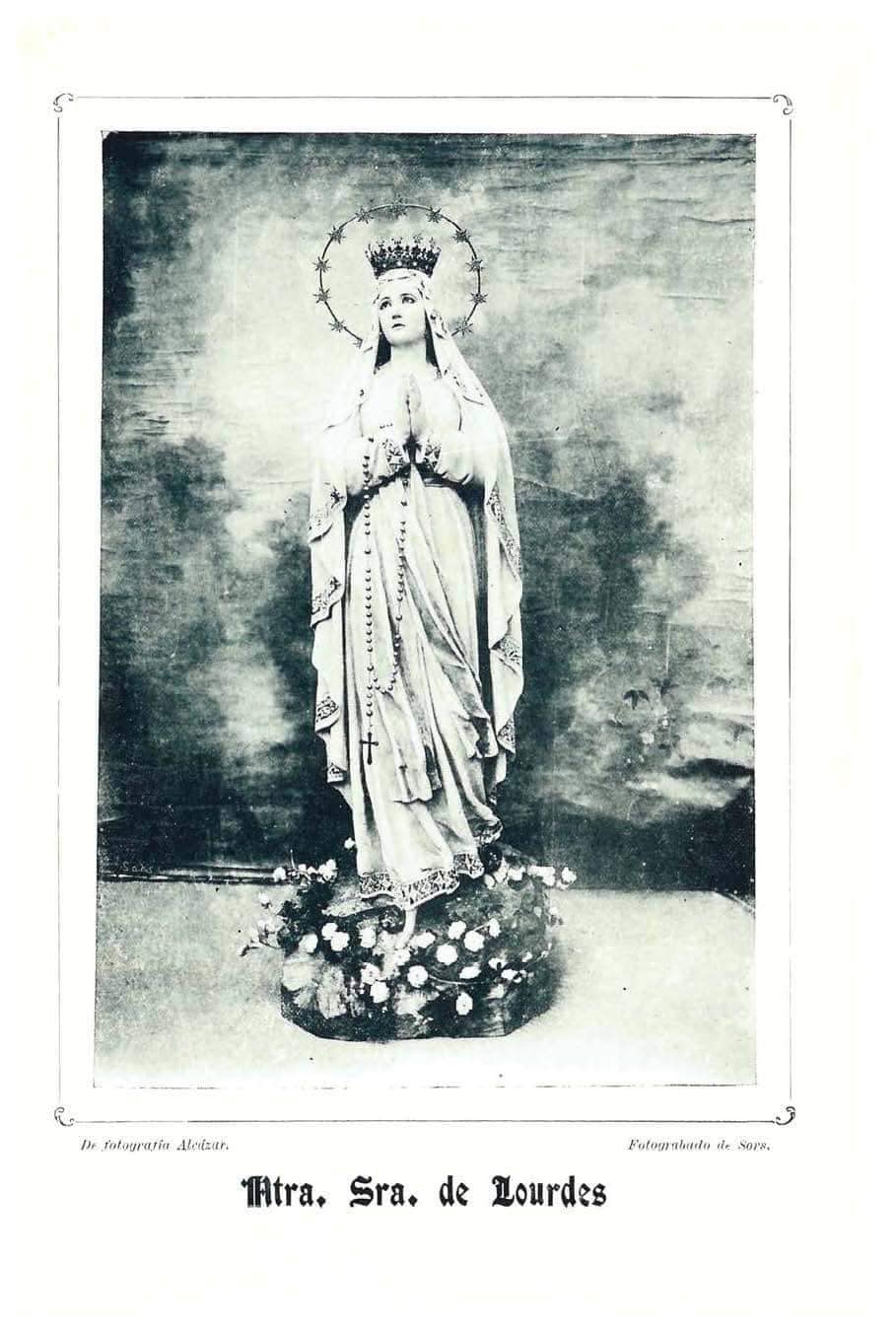

It was, however, not easy to obtain the necessary permission for the Canonical Erection of the Capuchin community in Intramuros. So, the Capuchins were, in a sense, technically simply Guests or worse still, “squatters” since they were not officially destined for the Philippines. Despite this handicap, the Capuchins opened a private chapel open to the public and, as already mentioned, dedicated to the Mother of the Divine Shepherd. In that same year, however, a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes (the same one venerated today at the left-hand side chapel of the Church in Quezon City) was placed within the chapel. And yet this one attracted more devotees! The ardent devotion of the Filipino people to the Virgin under this title was such that on September 15, 1893, the Confraternity of Our Lady of Lourdes was established and affiliated to the Archconfraternity of Lourdes, France, on February 11, 1896. And on August 26, 1910, Pope St. Pius X raised the Manila Confraternity into an Archconfraternity, thereby declaring that all other confraternities in the Philippines must be affiliated to this.

Capuchins as “… missionaries with equal status as the others, possessing all rights and obligations.”

A momentous event took place on August 17, 1896, when a Royal Decree emanating from the Spanish Crown arrived authorizing the installation of the Capuchins as “… missionaries with equal status as the others, possessing all rights and obligations.” By this declaration, the Capuchins stood at par with the other missionaries as it may be remarked that at that time, only five (5) Religious Congregations were allowed to do missionary work in the country. The five were, namely: Augustinians, Dominicans, Franciscans, Jesuits, and the Recollects.

Nuestra Señora de Lourdes

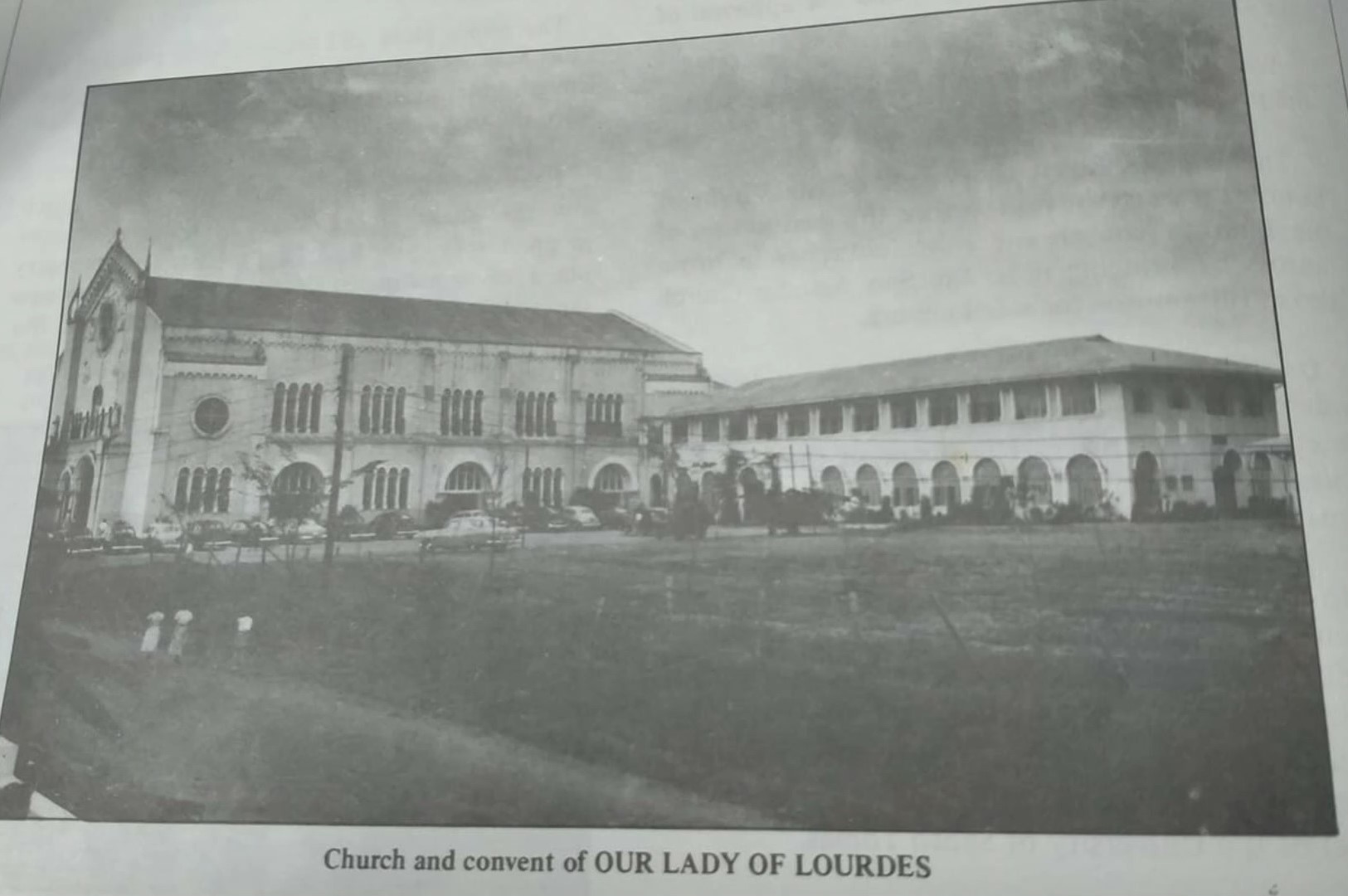

So with this new identity, the Capuchins took courage and began building a really big church within Intramuros to accommodate the growing number of devotees to Our Lady of Lourdes. In 1899, this church was dedicated to our Blessed Mother under the title of Our Lady of Lourdes. Unfortunately, this church was completely demolished by the bombardment of Manila by the US Air Force during the battle for liberation from the Japanese Imperial Army in 1945.

The aftermath of the Battle of Manila; Lourdes Church in ruins, 1945.

Nurturingthe Growth

As remarked earlier, the main purpose of the few Capuchins residing in Manila was to attend to the needs of their brothers working in the islands o0f the Carolines and Palaos. This determined the character of the residence in Manila: a “procura” house, something like a storage for supplies gathered expressly for sending out to the other islands at the same time a residence for the brothers coming and going to the islands in the Pacific. “Caritas Christi urget nos” when taken to heart makes people overflow with the desire to do something for building the Kingdom. Thus, the Capuchins took time to serve also the public chapel of Intramuros from whence the reception of the sacraments such as responding to the calls of the sick, teaching Christian doctrine through catechism sessions to children which began to demand more work and zeal from among the brothers, increased rapidly among the inhabitants. And Providence sent reinforcements. On June 27, feast of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, of 1901, another group of Capuchins arrived in Manila. But this time, the group had a different character in that these new arrivals was the first band of Capuchins expressly destined to work in the Philippines. These brothers were missionaries trained in the newly established missionary college of Lecároz under the direction and guidance of the famous Fr. Llevaneras, OFMCap.

The names of the friars composing this group are names that some of us may still vividly recall because our experience of these living persons who bore the names can still stir colorful evocations since the first-fruits of local vocations, namely us, can still remember our having received the sacraments from their ministry. Fr. Blas de Guernica (Vizcaya) Fr. Basilio de Guernica (Vizcaya) Fr. Roman de Vera (Navarra) Fr. Juan María de Ansoain (Navarra) Fr. Leoncio de Santibañez (Castilla) Fr. Mariano de Olot (Gerona in Cataluña) Br. Martin de Auza (Navarra) Br. Javier de Ituren (Navarra) Be. Serafín de Leaburu (Navarra)

From this time onwards and until the Japanese invasion and occupation, the subsequent expeditions of Capuchins were immediately assigned to the Diocese of Manila (later Archdiocese when Bulacan, Cavite, and Laguna were set-up as independent dioceses) as well as to other dioceses for the pastoral care of abandoned parishes and for missionary work of conversion or re-conversion. This move was due to the lack of pastors, especially in the hundreds of parishes abandoned by the Spanish missionary-friars of other religious congregations since the storm of the revolution broke out in 1898. That is how the Capuchins wandered as itinerant evangelists among the people from one diocese to another. They met a hostile populace simply because they were Spaniards, subjects of the resented Spanish government that was recently overthrown from power.

Bishops all over the country (few at that time) called upon the Capuchins mainly as preachers. Frs. Alfonso de Morentin, Ricardo de Torres, and especially Roman de Vera became famous in conducting Rural Missions mostly in Tagalog-speaking provinces as well as in Pampanga and Pangasinan. Such was the fame of the Capuchins in conducting retreats and popular missions that the Bishop of Manila, the American Msgr. Jeremiah Harty, pleaded with the Superior to allow some preachers to accompany him always in all his pastoral visits to the various parishes.

Setting upHouse.

It has been the experience of many of us when we begin to transfer residence or to renovate an old one that the first phases could be qualified and described as topsy-turvy or helter-skelter. Thus too the beginning of what is now the Capuchin Province of the Philippines. After the Suppression of all Religious Orders in Europe ended in 1886, the Restoration of Capuchin life began with the establishment of the District Nullius over the Capuchins for the entire Iberian Peninsula in December 18, 1889. This District Nullius was dissolved in 1907 and the establishment of the various juridical circumscriptions which were traditionally called Provinces were canonically effected. Because of this, many missionaries were recalled and returned to their original geographical pertinence. And so the Philippines came under the jurisdiction of Cataluña in August of 1907. For the next seven years, the Catalans tried but finally found it impossible to send enough missionaries to the Philippines. So, therefore, in March of 1914, the mission to the Far East was then entrusted to the newly restored Province of Navarra-Cantabria-Aragon which immediately sent a big number of friars to work in the Philippines and the islands of the Carolines and Palaos. In the meantime the college at Lecároz was transferred to Extramuros in Pamplona beside the winding blue-green waters of the river Arga.

During all these years until the Japanese occupation in 1941, the Capuchins from the Navarra-Cantabria-Aragon province continued their work, helping the bishops in the parish apostolate, spiritual retreats, holding popular missions in rural areas, and teaching the Christian doctrines. Another activity that developed during this time was their service to hospitals as chaplains. In their preaching, they opposed the erroneous teaching of the Aglipayan schismatics and the Arianistic sect of Felix Manalo who called themselves Iglesia ni Cristo. They also published and circulated a magazine entitled “El Antipoda” edited by Fr Roque de Azcoitia to combat and counteract the erroneous teachings of Masonry. Another magazine entitled “Estudio” explaining the authentic truths of the Catholic faith came out regularly. Several grammars and other literary works in books were also the fruit of the intellectual labors of the Capuchins of the time.

An important decision for the future of the Capuchins was taken in favor of the expansion to the north of Manila was taken in 1929. On the strength of this decision, they undertook the parish of San Miguel in Tarlac. Then followed other parishes in Pangasinan: Aguilar, Bugallon, Labrador, Salasa, and Sual in quick succession. They did a tremendous missionary work in these areas, learning the language, and continued to serve the people heroically especially during the Japanese occupation of World War II. The Capuchins served this sector of Pangasinan for thirty (30) years until they gave back an organized church community to the Bishop in 1960.

Rites ofPassage

This flourishing enterprise in favor of the People of God was subjected to a severe baptism of fire at the onset of World War II concretized in the invasion of Japanese and its Korean mercenaries. The Philippine mission, which became a Custody in 1937, lost nine brothers to the atrocity of the Japanese overlords: six were killed in Intramuros and three in Singalong.

As said earlier, the church dedicated to the Blessed Mother under the title of Our Lady of Lourdes, together with the mother-house along with the archives and library in Intramuros was completely destroyed and precluded any attempt at rebuilding. The parish of Ermita suffered the same fate. Fortunately, the statue of Our Lady as she appeared to St. Bernadette at the grotto of Lourdes remained unscathed. Now another footnote to this is that this statue had a twin that the original sculptor kept at his home in Pampanga. During the war, a relative of the sculptor tried to save the statue and brought it with him to Davao where it is still found in the replica of the grotto at the garden of residence of this relative. The residence is there behind the church of San Isidro Labrador in Catalunan Grande where the Capuchins were able to purchase a property overlooking the Talomo River. So like her sons who were always wanderers, she also began her trek so that the statue was brought during the war-years to the church of San Agustin in Intramuros where she stayed there as her temporary home for safe-keeping. After the war, the statue was brought to the small chapel of the parish of Sta. Teresita del Niño Jesús while a larger shrine was being built nearby along the road leading up to the cave used as a retreat by San Pedro Bautista across the creek. When the church that was supposed to serve a shrine to Our Lady was finished in 1951 beside the road that was then named Retiro Street, the statue was finally enshrined there.

“… UNLESS THE LORD BUILDS … “

In the meantime, new groups of Capuchins from the Province continued to arrive so that the work of reconstruction began. New times, new directions or as the Gospel says “new wines in new wineskins.” The decade after the war saw the increase of the diocesan clergy and the lack of sufficient number of personnel among the Capuchins adequate to respond to the rapid increase in the volume of work. This reality prompted the giving up of several parishes in the central plains of Luzon such as Tarlac and Pangasinan. Add to this the double difficulty of learning the English language as it replaced the Spanish and of several local languages such as Pampango, Ilocano, Pangasinense, and Tagalog so that the newly arrived Capuchins could not work effectively.

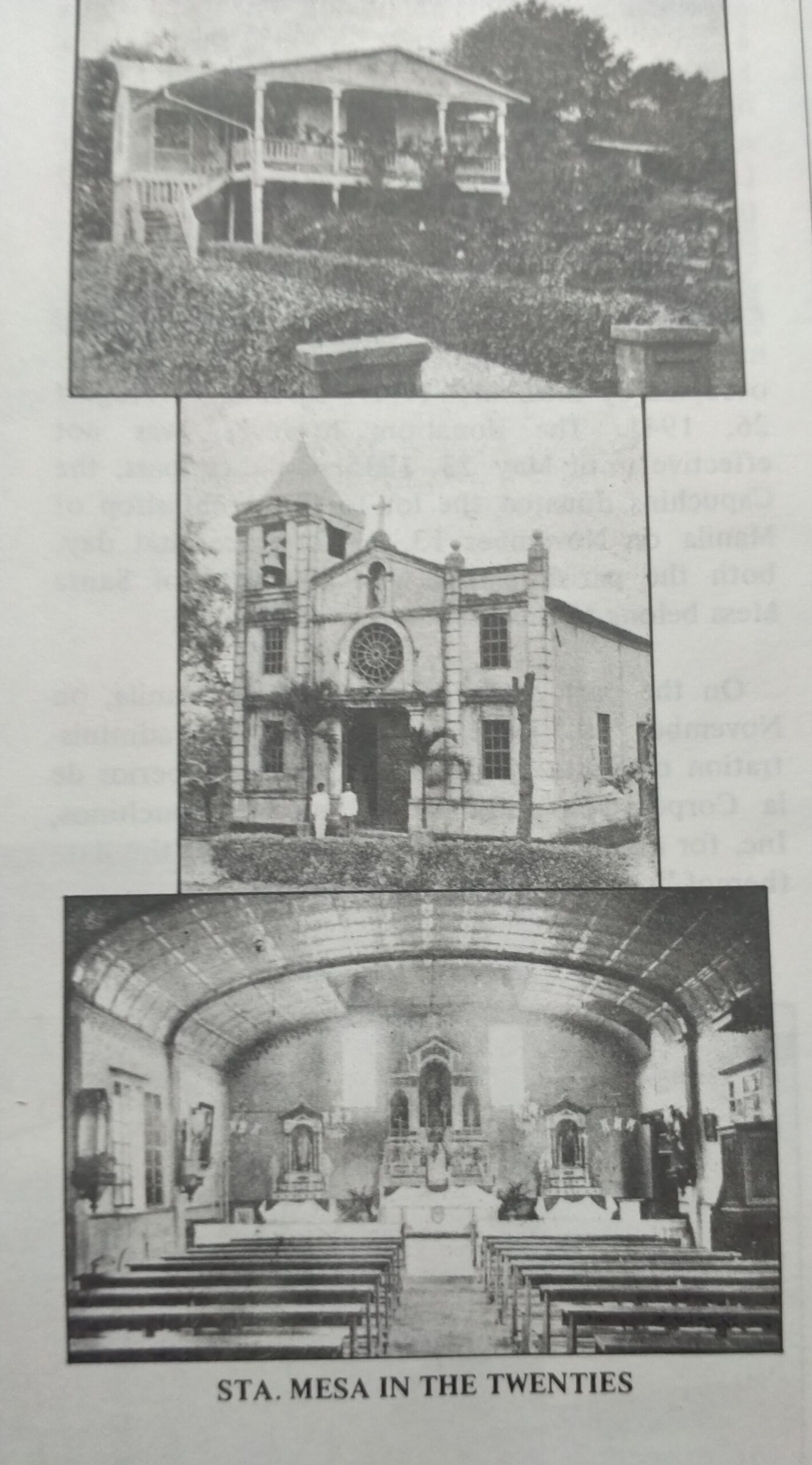

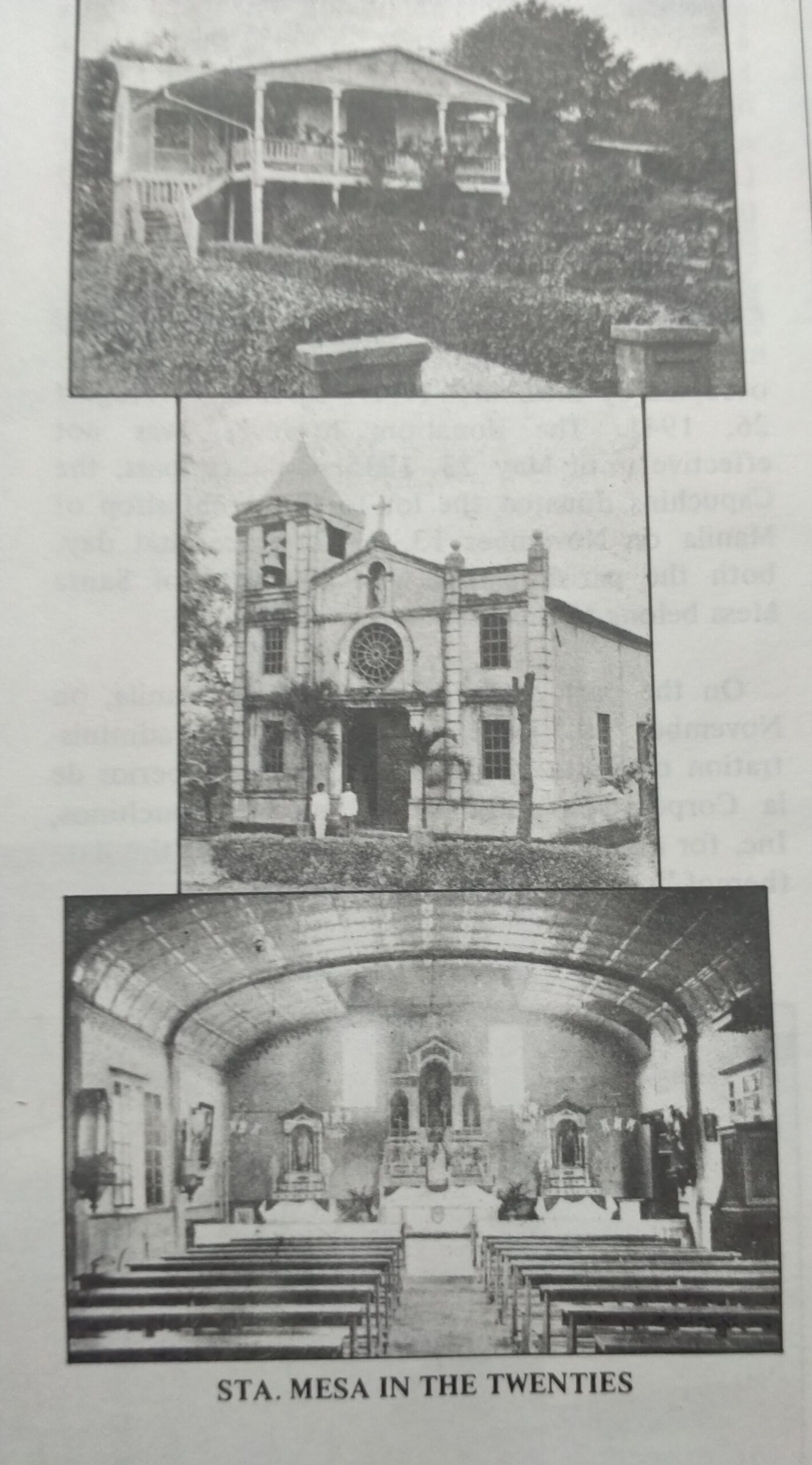

They simplified the problem by concentrating on learning Tagalog as they decided to work solely in the Tagalog-speaking provinces: Tagaytay City in Cavite (1939); retaining Singalong, in the San Andres district in Manila since 1904; in Quezon City by taking up work in Sta. Teresita along Mayon Street (1942); in Lourdes Church along Retiro (1951); Mandaluyong fronting Shaw Blvd. (1958); in various towns in the Bundok Peninsula of Quezon Province: Tagkawayan, San Narciso, San Andres (1959); Lipa City in Batangas (1966); and Pulo, Cabuyao, in Laguna (1970). The Capuchins also saw the needs of the country in the field of education especially of orphans and the poor before the war so they put up the parochial school of St Anthony in Singalong (1936). But the need was more so during the years immediately following the disastrous war which ended in1945. Thus was built the parochial school dedicated to the Sacred Heart in Sta. Mesa, Manila (1947); Lourdes School in Quezon City (1954); and Lourdes School in Mandaluyong (1959).

“The Lord SendsOther Disciples."

However, one may note the following regarding all these activities. Everything was carried out and accomplished by foreign missionaries from the Provinces of Navarra, the Cantabria region among the Basques and Aragon. Realizing therefore that the Lord works incarnationally and that effective inculturation in the implanting the charism can only be benefitted by homegrown vocations, the Capuchins assumed future-oriented decisions and were also “helped” along unexpectedly by two extraneous world events that still were fully within the Providence of God. Right after World War II, the last Capuchin foreign bishop of the Marianas with seat in Guam made his way back home to Spain and to take up again his lifestyle as an erstwhile Capuchin friar. Simultaneously, another bishop of a Diocese of Kansu administered by the Capuchins was forced to leave the diocese and out of China by the victorious communists led by Mao Zedong. So these two events signaled the shift in geopolitical forces whose effects were also reflected in the Capuchin Order. The islands of the Carolines and the Marianas in the Pacific became a United States’ Protectorate. And the U.S. government asked the Pope to replace foreign missionaries with Americans. China, in its turn, closed its doors to foreigners, most especially against foreign missionaries. The laws banning other religions especially Christianity are still in force today as long as the Communist Party remains in power.

The Capuchins, therefore, made a momentous decision to remain on Philippines soil and raise local or homegrown vocations as the first step in a serious implanting of the Order’s charism and to make its contribution of the religious Capuchin-Franciscan charism to the local church. Although the history of the formation of local vocations requires a process to the peculiar Capuchin way of life merits its own full-fledged retelling of its story, an initial remark on the process and its stages has to do with practically the same characteristic that other aspects of Capuchin life and history in the Philippines possesses: the mark of itinerancy.

Many other geographical places could be mentioned as part of the initial stages of the formation of early vocations to Capuchin life among the nationals, but the general presentation would necessarily be few. Among those centers would include: the San Carlos Diocesan Seminary in Guadalupe Viejo in Manila beside the Pasig River; the Our Lady of the Angels of the Alcantarine-Franciscans of the Philippine Province of St. Gregory in Bagbag, Novaliches; the St. Anthony School of Philosophy in Quilon, Kerala and the School of Theology in Tamilnadu, both in India; and the Missionary College of Pamplona in the civil province Navarra. This last in Spain is where we might say that we have come full circle.

1986 – THE FIRST HUNDRED YEARS

By this time, April 23, 1985, one day shy of the feast of the Proto-Martyr of the Propaganda Fede, St. Fidelis of Sigmaringen, the Philippines has reached the status of a fully developed independent Province in its own right. By this declaration, the Provincial Minister was conferred the right to sit on equal terms as the other Provincials at the General Chapter of the Order.

Statistically, however, the Province perhaps could not boast of impressive statistical figures but it showed elements that were a far cry from the five (5) Capuchin brothers who lived in a grass hut in the plains of the old Manila near the ports from where the ghosts of the ships of the Galleon Trade between the Spanish Empire’s colonies of the Philippines and Mexico set sail and docked. In 1985, eleven fraternities constituted the new Province. There were five (5) fraternities within the Greater Manila are, namely, Singalong, Sta. Mesa, Sta. Teresita, Lourdes Quezon City and Lourdes Mandaluyong. The six (6) others were located in the surrounding Ilocano-speaking and Tagalog-speaking provinces, namely: Tagaytay City; Sungay, Tagaytay City; Lipa City; Pulo, Cabuyao, Laguna; Baguio City; Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte.

The new Province had a man-power of sixty-nine Capuchin professed brothers. Of these sixty-nine, there were ten (10) brother-priests from Spain for the non-priests or lay-brothers had already returned home. Forty-six (46) were Philippine nationals forty-one (41) of whom were priests and one (1) lay-brother in perpetual vows; and thirteen (13) were in temporary profession of whom nine (9) were destined for ordination to the priestly ministry and four (4) for the lay-brotherhood.

The ministries in the new Province may be appreciated in the various concerns that take up much of the time and effort. First, since the effort of implanting the Order on Philippine soil is a never-ending effort, the work of formation in and for our way of life is of primary importance although the length and manner may vary. So the various stages would focus first on the initial introductory dynamics: The initial stage takes place in Lipa City. Second, The official dynamic of initiation which is of supreme importance is the Noviceship of one who has discerned his life’s calling as a Capuchin Religious is done in the Novitiate house of formation in Baguio City. Third, academic preparation for ministry is then taken care of in the St. Lawrence of Brindisi House of Studies in Tagaytay City by frequenting the academic disciplines at the nearby Divine Word Seminary of the Society of the Divine Word.

Fourth, Administration of Parishes some of which have Schools attached to them: Lourdes Convent in Quezon City – Parish and School (Elementary and High School); Sta. Mesa – Parish and School Singalong – Parish and School (Elementary and High School); Sta. Teresita – Parish only; Pulo – Parish only Tagaytay City – Parish only. Attention to the contemplative dimension of our life in the hermitage of Dávila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte Evangelical Witness of Presence in Baluan, General Santos, South Cotabato, where they live among farmers and doing farming work and helping out the diocesan clergy in sacramental ministry. Traditional missionary life and work while collaborating with American Capuchin missionaries from Province of Pittsburgh in Papua-New Guinea. Care of temporary immigrant overseas contract workers in Saudi Arabia, other Arab countries such as Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates as collaborative service together with other Capuchins from the United States, Italy, Lebanon, and various Provinces in India, to the church in the Diaspora.

Nota Bene:

This present article is a revised version of the original published on occasion of the Centennial Celebration of Capuchin Presence in the Philippines on May 1986. Publihed: August 8, 2019 by Br. Joseph Nacua OFMCap., D.D.